Featured image: Adoration of the Sheperds. Matthias Stom, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Key Takeaways

- Pagan Roots: Early Christmas traditions absorbed winter solstice customs from Pagan festivals.

- December 25 Choice: The Church selected December 25 to align with existing celebrations of the sun’s rebirth.

- Symbols Reinterpreted: Common Christmas symbols like evergreens and holly once held Pagan meanings before gaining Christian context.

- Global Adaptation: Over time, Christmas incorporated local customs and became a worldwide, multi-faceted holiday.

- Sacred and Secular Blend: Today, Christmas balances religious significance with commercial, family-focused, and cultural traditions.

Christmas stands as one of the most recognized and beloved holidays worldwide. Families and communities mark the season with gift exchanges, decorated evergreens, festive meals, and a spirit of goodwill. Beneath this familiar imagery lies a long, intricate history shaped by religious transitions, cultural blending, and the creative reimagining of old customs. While popular understanding often centers on the holiday as a commemoration of Jesus Christ’s birth, the Christmas we know emerged through a centuries-long encounter between Christian teachings and a range of earlier Pagan traditions.

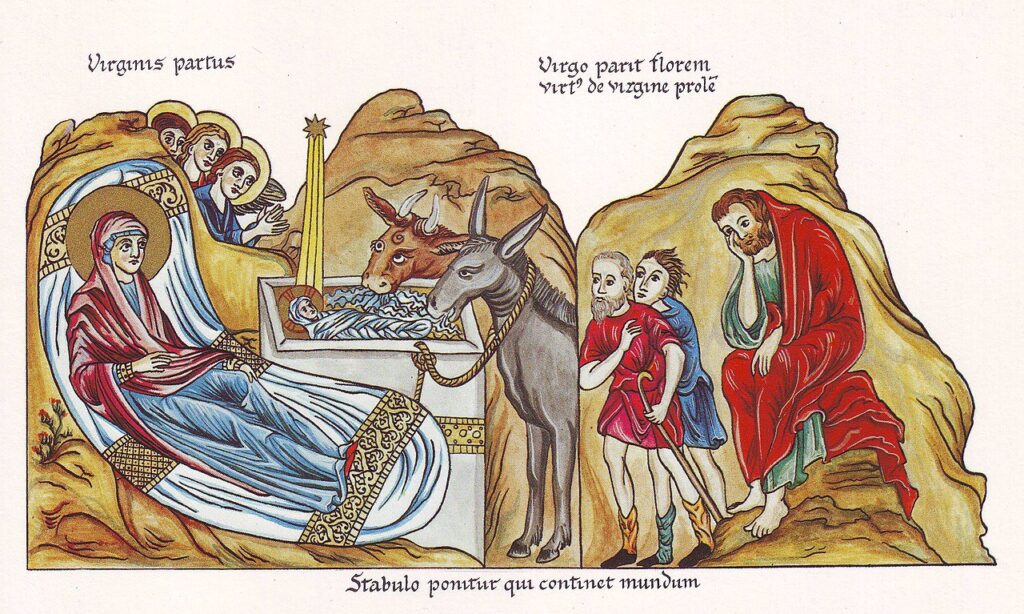

Long before the Nativity story took center stage, many cultures held winter festivals to honor the rebirth of the sun and the promise of renewed life after the darkest days of the year. Early Christian communities adapted these pre-existing traditions, aligning them with their theological narratives. Over time, new layers were added as the holiday passed through different regions, encountered fresh influences, and responded to shifting social values.

In today’s world, Christmas transcends religious boundaries. It appears in places and contexts far removed from the original Christian framework. The holiday’s symbols, rituals, and imagery encourage reflection on universal themes—hope, generosity, community, and renewal. Understanding its Pagan roots and Christian adaptations provides a window into how traditions evolve and why certain celebrations hold enduring appeal.

This article will explore how ancient Pagan solstice customs provided the groundwork for what became Christmas, examine the strategic choices early Christians made in selecting December 25, and trace the rich tapestry of symbols that link today’s festivities with rites thousands of years old. It will also consider the ways Christmas has been reinvented, commercialized, and transported across cultures, as well as the ongoing conversation about how best to honor its sacred origins and inclusive character.

Table of Contents

The Winter Solstice: Ancient Celebrations of Light and Renewal

Before the rise of Christianity, midwinter events flourished across Europe and beyond. The heart of these festivals lay in the winter solstice, the darkest point of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. Around December 21–22, the days begin to lengthen, signaling the gradual return of the sun’s warmth. Agricultural communities tied their survival to nature’s rhythms, making the solstice a symbol of hope and the promise of brighter days ahead.

Yule in Germanic and Scandinavian Traditions

In northern Europe, peoples of the Germanic and Scandinavian regions honored Yule. During these festivities, communities lit bonfires to coax back the fading sun, decorated their homes with evergreens to represent life enduring through the cold, and shared abundant feasts. The Yule log, burned through the season, promised good fortune and protection. Although these rites predated Christianity, elements such as bringing evergreens indoors would later appear prominently in Christmas traditions.

Roman Saturnalia: Feasting, Gift-Giving, and Social Upside-Down

In ancient Rome, mid-December brought Saturnalia, a festival dedicated to Saturn, the god of agriculture. Saturnalia turned ordinary social hierarchies on their heads. Masters and servants reversed roles, and people of all classes joined in street parties, public banquets, and gift exchanges. Candles and small tokens passed between friends and family helped brighten spirits during the darkest days. This joyful emphasis on community, equality, and abundance resonated across time, influencing how Christians would later structure their winter holiday.

Dies Natalis Solis Invicti: The Unconquered Sun

Late in the Roman Empire, December 25 marked Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the “Birth of the Unconquered Sun.” This festival honored the strength of the sun’s return, aligning light’s triumph over darkness with a crucial point in the calendar. By celebrating the sun’s resilience, Romans affirmed the natural order’s capacity for renewal. This emphasis on the sun’s birth would later inform the Christian choice of December 25 as the date of the Nativity—an occasion that could symbolically mirror the sun’s rebirth through the figure of Jesus as a source of spiritual light.

Early Christianity and Pagan Influences

Integrating New Beliefs into Old Contexts

As Christianity spread through the Roman Empire, it encountered an established religious and cultural landscape. Missionaries and Church authorities needed strategies to engage communities familiar with centuries-old Pagan festivals. Rather than demanding a wholesale rejection of beloved festivities, the Church allowed existing symbols, dates, and customs to remain, infusing them with Christian significance. This approach, often called syncretism, allowed converts to retain cherished traditions while embracing a new religious framework.

Deciding on December 25

The Bible does not specify the date of Jesus’ birth. In the early centuries, Christians did not universally celebrate the Nativity. However, by the 4th century, the Church settled on December 25. This date strategically overlapped with Dies Natalis Solis Invicti. Early theologians drew parallels between Christ and the sun, evoking passages like Malachi 4:2, which calls the Messiah the “Sun of Righteousness.” By placing Jesus’ birth close to the solstice, Christians could claim the auspicious symbolism already familiar to Pagan audiences. Light overcoming darkness—an ancient theme—found a new home in a Christian context.

Reassigning Meaning to Pagan Symbols

Ancient communities associated evergreens, holly, ivy, and mistletoe with fertility, endurance, and the cycles of life. Yule logs and greenery brightened cold interiors during the harsh winter months. When Christians adopted these customs, they reframed the symbolism. Evergreen branches and decorated trees were no longer just a nod to nature’s persistence; they now stood for eternal life in Christ. Over time, these symbols, once linked to Pagan rituals, became hallmarks of Christmas décor, lending the season a timeless resonance.

Pagan Elements That Persist in Christmas Traditions

The Evergreen Tree: From Forest Ritual to Festive Centerpiece

Evergreen trees, integral to Yule festivities, signified life triumphing over winter’s deathlike grip. Germanic and Norse cultures brought these trees indoors, honoring the green leaves that refused to fade. By the Renaissance, German families had begun decorating indoor evergreens with candles and small ornaments. This practice spread throughout Europe, and later to North America, evolving into today’s Christmas tree tradition. While few now think of Pagan forests or ancient rites, the vibrant, decorated tree in the living room still whispers of a distant past when nature’s endurance inspired wonder.

Yule Logs: Warmth, Fortune, and Community

The Yule log, a large piece of wood burned during winter gatherings, symbolized warmth and hope. Families kept it lit through the holiday, believing it brought good luck and drove away misfortune. With Christianization, the Yule log persisted, though its Pagan associations faded from collective memory. Some households maintain this tradition, and the log even inspired the French dessert known as the “Bûche de Noël.” Such customs show how easily a symbol can shift, carrying forward the human desire for comfort, continuity, and connection.

Holly and Ivy: Adorning Christian Homes with Ancient Greenery

Holly and ivy, both evergreen plants, feature in many midwinter festivals and folklore. Pre-Christian societies admired their resilience, linking them to fertility and protection. Early Christians integrated these plants into church decorations, reassigning them new layers of meaning. Holly’s prickly leaves, once a Pagan protective charm, came to represent the crown of thorns worn by Jesus, while its red berries evoked his blood. Ivy’s clinging growth suggested faith’s steadfast nature. In this way, ordinary plants bridged cultural and theological divides.

Gift-Giving: Echoes of Saturnalia

The festive exchange of gifts, a crucial part of Saturnalia, migrated into Christian tradition. During Saturnalia, Romans gave candles, figurines, and sweets to spread cheer. As Christmas gained prominence, gift-giving took on a Christian dimension, reflecting the Magi’s gifts to the Christ child. Over time, this practice expanded, influenced by local custom and economic growth. Today, the gift-giving frenzy that defines modern Christmas shopping might obscure the older roots, but the custom’s emphasis on generosity and community harks back to ancient streets filled with laughter and exchanged tokens of goodwill.

Santa Claus and Odin’s Legacy

The character now known as Santa Claus draws from diverse sources, including the historical Saint Nicholas of Myra and European folklore figures. Some scholars highlight parallels between Santa’s mythical features and the Norse god Odin, who rode through the winter skies during Yule, rewarding the worthy. This fusion allowed older mythological motifs to persist under new guises, blending stories of kindly bishops, flying reindeer, and an enchanted Christmas Eve. While many see Santa as a modern, secular figure, he carries echoes of ancient divinities and seasonal spirits.

The Christianization Process: Theology and Practice

Jesus as the “Light of the World”

By adopting December 25, the Church invited believers to view the birth of Jesus as a metaphysical dawn following a time of darkness. This narrative resonated with traditional solstice symbolism. Pagan observers of the sun’s rebirth found a comparable theme in Christianity’s promise: a spiritual light illuminating the human condition. Sermons and hymns emphasized that the coming of Christ paralleled the sun’s return, imbuing the winter feast with theological depth.

Integrating Local Customs into Christian Worship

As Christianity spread across Europe, missionaries adapted the holiday to suit local tastes. In areas influenced by Germanic and Scandinavian customs, Yule elements found their way into the Christmas calendar. Caroling, which started as part of Pagan winter festivities, evolved into Christmas hymns sung door-to-door. Dramatic reinterpretations of Pagan storytelling led to Nativity plays, reinforcing the season’s sacred message. This pattern of incorporation and reinterpretation ensured Christmas would not feel like a foreign imposition but rather a meaningful enhancement of existing celebrations.

Church Endorsement and Liturgical Formalization

By the Middle Ages, the Church had firmly embedded Christmas in its liturgical cycle. Midnight Mass, elaborate pageants, and devotional practices centered on the Nativity story underscored the holiday’s religious character. Over time, Christmas took root as a cornerstone of Christian identity, yet some Church leaders expressed concern about lingering Pagan elements and excessive merrymaking. Indeed, the tension between sacred devotion and festive revelry runs through Christmas’ long history.

Challenges, Reformations, and Shifts in Christmas Observance

Puritan Resistance and Temporary Bans

In the 17th century, certain Protestant reformers, including Puritans in England and colonial America, identified Christmas as an over-commercialized, Pagan-influenced event. They argued that the Bible did not mandate this celebration, and they disapproved of its rowdy character. As a result, Christmas faced bans or official discouragement in places like Puritan Massachusetts. These attempts to cleanse the holiday of its “un-Christian” influences did not last permanently, but they highlight how Christmas has repeatedly been contested and reshaped over the centuries.

The Victorian Revival of Christmas

By the 19th century, a revival began that would redefine Christmas into something more family-centered and morally uplifting. In England, writers like Charles Dickens portrayed Christmas as a time of empathy, charity, and domestic warmth. A Christmas Carol (1843) helped craft a modern understanding of the holiday as a moral lesson in kindness and generosity. This Victorian vision recast Christmas from a sometimes boisterous affair into a quieter, family-focused celebration. Although many Pagan echoes persisted—trees, greens, and social gatherings—the emphasis now fell on good deeds, compassion, and the joys of home.

Commercialization and the Rise of Global Christmas

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw Christmas become increasingly commercial. Department stores recognized the holiday’s potential, dressing their windows with lavish displays and advertising toys and treats. Retail marketing campaigns urged consumers to buy gifts and decorations, creating an economic engine that helped Christmas spread. This commercialization allowed the holiday to take root in cultures beyond its Christian or Pagan origins. People could appreciate it as a festive season centered on gift-giving, cheerful gatherings, and sparkling décor, even if they did not share its religious background.

Secularization and Global Expansion

Christmas in Non-Christian Contexts

As Western influence expanded, Christmas found new homes in places with different religious traditions. In Japan, for example, Christmas is observed as a secular festival, celebrated with illuminated streets, gift exchanges, and special meals. In India, Christians celebrate within their communities, but those of other faiths may join in by exchanging sweets or decorations. The adaptability of Christmas traditions—especially the fun, gift-oriented aspects—makes them appealing and easy to adopt.

Cultural Fusion: Local Twists on a Global Holiday

Every society that embraces Christmas adapts it to match local tastes. In Mexico, Las Posadas processions reenact Mary and Joseph’s search for shelter, grounding Christmas in a communal story. In the Philippines, Simbang Gabi involves a series of dawn masses and festive foods, blending devotion with joyful eating. In these ways, Christmas acts as a cultural chameleon, melding with regional practices and fostering new holiday identities.

Media, Music, and Movies

The 20th century’s mass media revolution played a crucial role in popularizing Christmas. Films like It’s a Wonderful Life and songs like “White Christmas” gained global traction, promoting themes of family, nostalgia, and benevolence over purely religious narratives. Pop culture embraced Christmas’ cheerful aesthetic and sentimental core, allowing viewers and listeners from many backgrounds to enjoy its mood. In these cultural products, the holiday’s Pagan and Christian roots appear indirectly, overshadowed by universal messages of hope and human connection.

Balancing the Sacred and the Secular

The “True Meaning” Debate

As Christmas became a global phenomenon, debates about its “true meaning” intensified. Religious observers seek to preserve its spiritual essence, reminding believers that the holiday commemorates Christ’s birth and its profound theological message. At the same time, non-religious enthusiasts see Christmas as an opportunity to celebrate family, generosity, and the comforts of winter. The tension is not new; rather, it reflects the holiday’s capacity to serve multiple purposes.

Consumerism vs. Charity

Critics argue that heavy commercialization has overshadowed Christmas’s moral and spiritual dimensions. Glitzy decorations, expensive gifts, and marketing campaigns can push the original themes of light, hope, and renewal into the background. Yet, every year, charities report increases in donations and volunteer activity during December. Even in its heavily secularized form, Christmas encourages generosity. The same impulse that once inspired Pagans to share feasts and Romans to exchange small gifts continues to prompt people to help neighbors and strangers today.

Interfaith Participation

Christmas traditions, stripped of their doctrinal weight, offer a platform for interfaith and intercultural engagement. Secular-minded families or those from other religious traditions can enjoy the season’s culinary specialties, music, and social gatherings. People may attend a holiday concert, visit a Christmas market, or admire neighborhood lights without engaging with the religious meaning. This flexibility allows Christmas to foster intercommunity understanding. It stands as an example of how traditions, even those rooted in a specific faith, can take on broader cultural roles.

Comparative Reflections: Universal Themes and Shared Humanity

Light Over Darkness

One of the most consistent themes linking Pagan solstice rites, early Christian Nativity celebrations, and today’s global Christmas observances is the victory of light over darkness. Whether celebrating the rebirth of the sun, the coming of Christ’s spiritual illumination, or the general idea of hope at year’s end, communities worldwide find common ground in the return of brightness. This cycle resonates with universal human experiences of hardship, endurance, and relief.

Renewal and New Beginnings

Many winter festivals—ancient and modern—emphasize renewal. Solstice traditions looked forward to growing days and better harvests. Christianity interpreted the birth of Jesus as a new beginning for humanity. Secular celebrations welcome the New Year, signaling a fresh start. Across time and place, people have found inspiration in the idea that after hardship comes regeneration. Christmas and its Pagan ancestors teach that even in deep winter, the seeds of spring remain hidden, ready to bloom.

Generosity, Community, and Shared Joy

The spirit of giving, hospitality, and shared merriment we associate with Christmas echoes themes found in countless other winter festivals. From Saturnalia’s gift exchanges to the communal feasts of Yule, these customs remind us of our intrinsic need for fellowship. Today’s Christmas gatherings may feature parties, charitable drives, and community events, reinforcing the idea that celebrating together can help us endure difficult seasons and strengthen bonds.

The Adaptability and Resilience of Christmas

One reason Christmas endures across centuries and continents is its capacity to adapt. It began as a fusion of solstice festivities and Christian theology, evolving over time to incorporate local customs, creative reinterpretations, and modern economics. Its symbols, such as evergreens, convey layered meanings—once Pagan, then Christian, and now often simply festive.

Christmas also inspires a sense of nostalgia that many find comforting. This nostalgic quality draws on centuries of storytelling, music, and imagery. Even as the holiday transforms to fit contemporary lifestyles, it retains a familiarity that people find reassuring. The adaptability of Christmas proves that traditions can remain meaningful by embracing change and seeking relevance for new generations.

Christmas Today: A Bridge Between Past and Present

Today’s Christmas blends past and present, myth and faith, commerce and devotion. It links distant Pagan forests and Roman feasts with modern living rooms strung with twinkling lights. The holiday’s success in reaching across ages and cultures stems from its open-ended symbolism and willingness to absorb new influences.

For religious observers, Christmas is a pivotal marker of faith, a time to contemplate mysteries of incarnation and divine love. For secular communities, it offers color, warmth, and reasons to connect after a long year. Both perspectives are authentic responses to a holiday that has always worn many hats.

Exploring these layers reveals a fundamental truth: traditions do not exist in isolation. They emerge from dialogue among peoples, beliefs, and environments. By examining how Christmas took shape—beginning with Pagan solstice festivals, evolving under Christian influence, and traveling worldwide—we gain insights into human creativity and shared heritage.

Conclusion

Christmas stands at the intersection of ancient rituals and modern practices, weaving together the threads of Pagan solstice celebrations and Christian theology. Its early formation relied on strategic alignment with familiar midwinter customs, allowing new converts to find comfort in old symbols reframed with Christian meanings. Over time, the holiday absorbed regional variations, grew into a family-focused and commercially vibrant season, and expanded globally, meeting local communities on their own cultural ground.

The enduring appeal of Christmas lies in its ability to speak to basic human impulses: to celebrate light in darkness, to mark transitions, to strengthen social ties, and to hope for renewal. While debates persist about the balance between religious observance and secular enjoyment, Christmas continues to thrive as a multifaceted holiday. Each generation reimagines its customs, forging a dynamic legacy that honors the past while adapting to the present.

In the end, Christmas illustrates how cultural traditions evolve through blending, borrowing, and reinventing. By tracing the festival’s Pagan roots and Christian adaptations, we gain a deeper understanding of its universal relevance. Whether one approaches Christmas as a sacred feast or a cheerful, inclusive gathering, the season’s richness lies in its layered history—a testament to humanity’s capacity for creativity, adaptation, and shared celebration.