Featured image: Saint Michael. Besenbinder, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Key Takeaways

- Christian myth communicates deeper insights than factual statements alone can reveal.

- Karl Jaspers views myth as a symbolic path that points to truths beyond direct logic.

- Rudolf Bultmann’s demythologization emphasizes existential meaning over literal accounts.

- Paul Tillich highlights the power of religious symbols for expressing the depth of human experience.

- Comparative scholars like Mircea Eliade and Joseph Campbell show that universal themes underlie Christian narratives.

The stories, symbols, and images woven into Christianity have long inspired inquiry and devotion. They stand at the crossroads of culture, history, and literature, shaping collective memory as well as individual outlooks on life. These narratives—often labeled as myths in academic and scholarly discussions—carry a depth that surpasses factual or rational explanation. They have given form to central Christian concepts such as creation, redemption, and salvation. Yet, in modern contexts, many readers encounter these accounts uncertain of whether to interpret them literally, reject them as outdated, or approach them as symbolic representations of reality.

This article examines how myth functions as a vital language within Christianity, drawing on the perspectives of major twentieth-century thinkers: Karl Jaspers, Rudolf Bultmann, and Paul Tillich. Each of them recognized the enduring power of Christian narratives for addressing profound human questions—those related to existence, morality, identity, and the longing for transcendence. Their insights highlight how myths are not simply fanciful tales but living symbols that connect believers and non-believers alike to deep truths about selfhood and community.

In the following sections, we will consider the meaning of “myth” in a Christian context, survey the historical interplay between myth and doctrine, and delve into how Jaspers, Bultmann, and Tillich illuminate these enduring narratives. In addition, we will look briefly at how Mircea Eliade and Joseph Campbell reinforce the view that religious myths speak to universal human themes. The final sections will reflect on how these ideas find renewed significance in today’s world.

Table of Contents

Defining Christian Myth

Myth in Religious and Cultural Context

Myth, as understood by scholars of religion, anthropology, and literature, does not simply imply a fabricated story. In academic study, myth often refers to narrative frameworks that provide meaning, purpose, and identity to a community. Myths address existential or cosmic questions: How did the universe begin? What is humanity’s role in the larger order of things? How does one find moral or spiritual guidance? These questions may not lend themselves to strict empirical answers, yet they remain central to human life.

Distinctive Aspects of Christian Myth

Christian mythology—encompassing narratives about Creation, the Incarnation, the Cross, and the Resurrection—reflects centuries of theological reflection and cultural development. Stories in the Hebrew Bible were absorbed into Christian tradition, evolving through interpretive layers as the faith spread across regions and eras. The New Testament Gospels add their own voice, presenting accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus. Over time, these stories took on new significance through art, liturgy, and theology.

Historians and scholars of religion point out that Christian myths function on multiple levels. They convey beliefs about God’s relationship to humanity, provide moral examples, and serve as sources of communal identity. They are found not only in the biblical texts themselves but also in apocryphal writings, legends of saints, and the rituals that developed around holy days.

Value of Mythic Language

Myth transcends bare factual data, tapping into imagination and symbolism to speak to deeper aspects of human consciousness. People often recall a story more vividly than a doctrinal statement. A symbolic narrative invites reflection on themes like hope, sin, love, and redemption, while literal statements might seem rigid or unchanging. As we proceed, the views of Jaspers, Bultmann, and Tillich will illustrate how myth, when treated with an open yet critical mindset, offers a bridge between the finite human world and the immeasurable mystery that many believers call the divine.

Brief Historical Context: Myth and Doctrine

Early Christian Communities and Oral Traditions

The earliest followers of Jesus met in small assemblies, sharing memories, hymns, and stories. These included parables, moral teachings, and miraculous accounts that circulated among various communities. Although the Gospels were written decades after the events they describe, they retained features of oral storytelling. These documents merged historical recollection, theological conviction, and mythic motifs to communicate their messages about Jesus as the Christ.

Institutionalization and Creeds

Over time, Christianity evolved from a grassroots movement to an institution with structured doctrines. Councils like Nicaea (325 CE) and Chalcedon (451 CE) sought to clarify core beliefs about the identity of Jesus. In this process, certain interpretations of biblical narratives became established as orthodoxy. While these doctrinal formulas offered unity of belief, they sometimes hardened interpretations of mythic language. Allegorical or symbolic readings continued, but there was also a rising emphasis on historicity, which in some instances overshadowed the more poetic and mystical elements of the tradition.

Mythic Threads in Liturgy and Art

Despite these doctrinal strictures, mythic strands remained central to Christian imagination. Icons of saints, stained-glass depictions of biblical events, and dramatic retellings of pivotal stories during liturgical feasts kept symbolic and imaginative elements alive. Seasonal celebrations—like Christmas and Easter—integrated local cultural traditions into Christian mythic narratives. This blending underscores that myth endures not only in authoritative statements but in the collective creativity of communities.

Modern Scholarship and Questioning

In the modern era, advanced textual criticism and historical research on the Bible brought new attention to the origins, authorship, and cultural settings of Christian texts. These developments posed questions about literal versus metaphorical truth, prompting theologians and philosophers to revisit the nature of myth. Jaspers, Bultmann, and Tillich emerge within this context, each offering nuanced approaches to understanding how Christian narratives reveal something greater than mere historical detail. Their work suggests that myths—far from being discarded or blindly accepted—can be interpreted so that believers and non-believers alike may engage more thoughtfully with Christianity’s central stories.

Karl Jaspers and Christian Myth

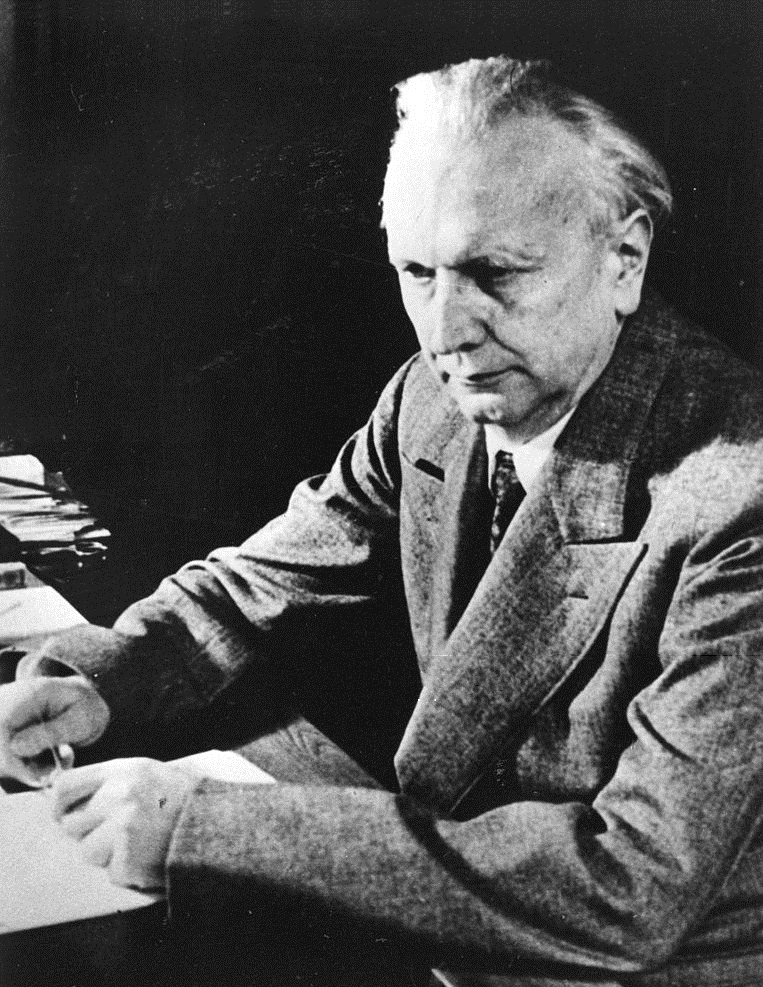

Jaspers’s Philosophical Background

Karl Jaspers (1883–1969) began his career as a psychiatrist, which informed his interest in the inner dimensions of human experience. He transitioned into philosophy, becoming a pivotal figure in existential thought. His works, including Philosophy and Philosophical Faith and Revelation, address the limits of knowledge and the ways in which humans relate to what he termed the “Encompassing” or ultimate reality.

Myth as Cipher

For Jaspers, a myth serves as a “cipher.” A cipher, in his usage, refers to a symbolic clue through which one might glimpse realities beyond the reach of purely rational methods. He viewed Christian stories—like the nativity narratives or the Resurrection of Jesus—as ciphers that speak to human life in profound ways, opening up an avenue for existential reflection. Jaspers did not insist on affirming or denying the literal truth of these accounts. Instead, he asked what these narratives reveal about hope, self-understanding, and the search for something beyond mundane experience.

Caution Against Literalism

Jaspers cautioned that an overly literal approach could rob myths of their deeper power. If a myth is taken strictly as an objective historical statement, it risks becoming a point of dogmatic contention. Under such conditions, the story ceases to challenge or inspire and instead becomes an unexamined formula. By keeping the mythical dimension alive, one allows the story to remain open, dynamic, and resonant with existential truths. Jaspers emphasized personal engagement: a receptive mind is required to unlock the wealth of meaning a myth can convey.

Relevance to Christian Tradition

Although Jaspers was not an official theologian, his perspective offers valuable insights for understanding Christian narratives. He recognized that believers regard the Bible as sacred, yet he believed that myths—religious or otherwise—must be open to interpretation. According to Jaspers, studying biblical texts philosophically allows one to move beyond a superficial reading. For example, reflecting on the Cross might prompt questions about sacrifice, suffering, and compassion rather than arguments over its historical details alone.

Legacy and Influence

Jaspers’s ideas about myth have influenced various fields, from philosophy of religion to depth psychology and hermeneutics. His stance encourages readers to treat traditional stories as pathways to existential meaning instead of mere vestiges of an unenlightened past. In sum, Jaspers’s framework respects the spiritual significance of Christian myth while also affirming that mythic language transcends dogma. It encourages a posture of inquiry, where faith does not demand the surrender of reason but invites an expansive encounter with the intangible.

Rudolf Bultmann’s Demythologization

Bultmann’s Scholarly Roots

Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) was a German Lutheran theologian known for applying historical-critical methods to the New Testament. He was trained in the era of form criticism, which sought to isolate and study the different literary forms within biblical texts. Through his close textual analysis, Bultmann identified specific mythic elements in the Gospels and Epistles, such as apocalyptic visions, demonic forces, and miraculous healings. He believed these elements were embedded in the worldviews of the first-century Mediterranean world.

The Approach of Demythologization

Bultmann contended that while the original audience of the New Testament took these mythical motifs for granted, modern individuals struggle with them. Instead of discarding these accounts, Bultmann proposed “demythologization.” This does not mean stripping the text of its meaning; instead, it means reinterpreting mythic language to highlight existential truths. For him, the core message of Christianity concerns the human predicament—anxiety, guilt, finitude—and the call to authentic existence through faith.

His famous example concerns the Resurrection. Rather than focusing on whether the event happened in a literal sense, he emphasized the Resurrection as a symbol of new life and transformative hope. This symbol invites believers to confront their own mortality and despair, opening themselves to renewed trust in what Christian tradition points to as divine grace.

Challenges and Criticisms

Bultmann’s program sparked substantial debate. Some theologians argued that in an effort to adapt the Gospel to modern sensibilities, Bultmann stripped away crucial historical underpinnings. Others supported his perspective, seeing it as a necessary engagement with modernity that allows Christian teachings to remain meaningful without conflict with science or history. Whatever the verdict, Bultmann set a milestone by calling for critical reflection on how best to read ancient texts in a contemporary world.

Common Ground with Jaspers

Bultmann’s project shares common ground with Jaspers’s view of myths as symbolic gateways. Both thinkers emphasize existential engagement over literal acceptance or dismissal. Both propose that myths address questions of ultimate meaning, inviting personal transformation rather than intellectual coercion. They challenge the assumption that one must choose between fundamentalist literalism and outright rejection of religious stories.

Enduring Significance

Bultmann’s influence extends into modern biblical scholarship, preaching, and theology, where conversation continues about how to reconcile ancient narratives with contemporary understanding. Whether one agrees or disagrees with his conclusions, his work underscores the possibility that myth can retain its power once reinterpreted in ways that speak to perennial questions of human existence.

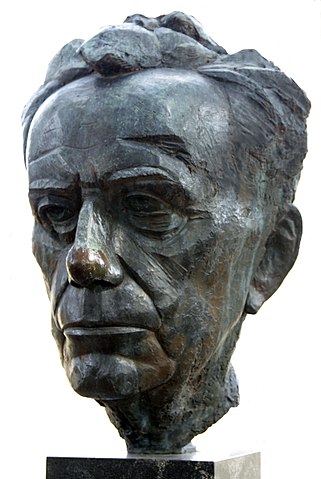

Paul Tillich and the Power of Symbol

Tillich’s Theological Vision

Paul Tillich (1886–1965), a German-American theologian, approached Christian thought from a philosophical standpoint that resonated with existentialism. He is well known for describing God as the “Ground of Being,” suggesting that the divine is not a separate entity or a superhuman figure but rather the very basis of existence. Throughout his writings, Tillich argued that religion operates through symbols that represent dimensions of life beyond direct articulation.

Myth and Religious Language

Tillich saw myth as an integral mode of religious expression. His work linked theological ideas with cultural, psychological, and aesthetic dimensions, implying that myths communicate essential truths in a form that rational discourse cannot fully capture. Rather than confining a story like the Creation narrative to a literal timeline, Tillich would emphasize its symbolic capacity to speak about the origins of purpose, the nature of existence, and humankind’s place in reality.

Symbol vs. Literalism

Tillich warned against two extreme reactions: dismissing mythical narratives as irrelevant on the one hand, or insisting on their literal truth on the other. He believed such positions can miss the deeper resonance myths hold. In his view, the power of myth lies in its ability to point beyond itself to God, human nature, and the sometimes hidden layers of life. A symbol draws attention to something greater, stirring emotions, thoughts, and spiritual awareness that purely factual statements may not elicit.

Resonance with Jaspers and Bultmann

Like Jaspers, Tillich saw myths as signposts to transcendence. Like Bultmann, he recognized the existential core of Christian teaching. Yet Tillich offered a specific language of “symbol,” integrating it with his theological system. In this framework, symbols are alive: they thrive as long as they continue to speak to people’s experiences. Once they stop doing so, they decay into outdated references. Thus, Tillich encouraged continuous reinterpretation of Christian symbols in each generation.

Cultural and Pastoral Dimensions

Tillich’s work also showed a pastoral concern. He believed faith should respond to real human struggles—anxiety, loneliness, guilt, and the search for meaning. By engaging Christian myth and symbol with an open mind, he believed communities can foster inclusive dialogue about life’s greatest challenges. Art, music, and other creative forms of expression can all be vehicles to interpret and re-energize traditional myths for contemporary settings.

In sum, Tillich’s emphasis on religious symbolism reinforces the view that Christian myth offers an indispensable language for addressing the depth of human existence. He saw these stories as channels for questions and hopes that all people share, regardless of creed or philosophical outlook.

Comparative Glances: Mircea Eliade and Joseph Campbell

Eliade’s Sacred and Profane

Mircea Eliade (1907–1986), a historian of religion, distinguished between the sacred and the profane in human experience. Myths, in his approach, act as a bridge that brings individuals into contact with the sacred dimension of reality. In Christian tradition, events like the Nativity or the Last Supper may be interpreted as moments where the sacred intersects ordinary life. For Eliade, this cosmic framework is universal: virtually every culture preserves stories that anchor people in a world charged with deeper meaning.

Campbell’s Hero’s Journey

Joseph Campbell (1904–1987), known for his comparative study of myths, highlighted the recurring “hero’s journey” motif. He identified this pattern across global cultures: a hero receives a call, faces trials, experiences transformation, and returns enriched with knowledge or power. Christian narratives about Jesus and the apostles resonate with such elements. Campbell pointed out that myths are not purely about distant figures; they mirror internal journeys of growth, sacrifice, and renewal for individuals in any era.

Connection to Christian Myth

Both Eliade and Campbell bolster the argument presented by Jaspers, Bultmann, and Tillich: myths carry enduring relevance because they engage universal human concerns. Christian myths, though rooted in particular historical circumstances, share archetypal motifs that connect believers worldwide to foundational questions about life’s purpose and the possibility of redemption. By comparing Christian stories with counterparts in other traditions, scholars underscore the rich tapestry of shared human imagination that myths encompass.

Contemporary Significance and Practical Reflections

Ongoing Cultural Presence

Even in societies that emphasize empirical data and scientific progress, Christian myths continue to shape cultural consciousness. Imagery from biblical narratives appears in literature, films, and visual arts, while references to figures such as the Good Samaritan or the Prodigal Son still resonate in everyday conversation. Such stories provide a narrative vocabulary through which many interpret moral dilemmas and collective values.

Personal Engagement and Interpretation

For those drawn to these narratives—regardless of religious affiliation—mythic language can spark ethical and philosophical reflection. Parables about mercy, sacrifice, or forgiveness resonate with universal questions about human behavior. Engaging mythic elements involves a willingness to ponder metaphors and symbolism, allowing them to speak to current social and personal challenges. In this sense, Christianity’s enduring mythic symbols become catalysts for dialogue on questions of justice, compassion, and hope.

Balancing Respect and Critical Thought

Analysts remain mindful of the sacred importance of these stories for many adherents. At the same time, critical study does not need to undermine reverence. Understanding historical contexts, narrative structures, and theological interpretations can deepen one’s appreciation of a story’s richness. This balance can be seen in academic approaches that respect tradition while applying insights from linguistics, anthropology, and literary theory to illuminate how and why myths resonate.

An Invitation to Inquiry

Reflecting on Christian myth may prompt questions for further investigation: How do these narratives intersect with one’s own life experiences or cultural background? What might they convey about love, suffering, or the quest for ultimate meaning? For some, these reflections may lead toward renewed spiritual commitment, while others may appreciate the stories’ literary or symbolic value. Either way, the ongoing vitality of Christian myth suggests that it continues to shape human thought and feeling across time.

Conclusion: Myth as a Vital Language

Explorating Christian myth through the works of Karl Jaspers, Rudolf Bultmann, and Paul Tillich illustrates that myth is neither a relic of superstition nor a simple factual report. It belongs to a category of human communication that speaks to the heart of reality, conveying what may not be fully articulated through logical discourse. Jaspers taught us that myths function as ciphers for transcendence, Bultmann showed how demythologization preserves existential depth, and Tillich underscored that such symbols direct attention to the very ground of human existence.

This triad of thinkers—along with scholars like Mircea Eliade and Joseph Campbell—reminds us that myth carries a power to address perennial questions about life, death, meaning, and community. Their approaches converge around the idea that myth serves as a vessel for truth that goes beyond historical detail. Whether one stands within or outside Christian tradition, these narratives can spark curiosity, empathy, and creative engagement with the broader human condition.

As the world continues to grapple with rapid cultural and technological shifts, mythic stories and symbols remain touchstones for understanding who we are and what we might aspire to become. The voices of Jaspers, Bultmann, and Tillich encourage readers to approach Christian myth with an attitude that appreciates its transformative potential. These stories endure precisely because they stimulate reflection on mystery, purpose, and hope—dimensions that remain at the center of human longing.

Suggested Resources and Further Reading

Primary Works

- Karl Jaspers, Philosophical Faith and Revelation

- Rudolf Bultmann, New Testament and Mythology

- Paul Tillich, Dynamics of Faith

Secondary Sources

- Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane

- Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

- Robert Segal (ed.), The Myth and Ritual Theory

These resources provide more in-depth perspectives on the role of myth in Christianity and its intersections with existential philosophy, biblical criticism, and cross-cultural studies. Engaging with them can expand one’s understanding of how mythic language functions as a bridge between historical faith traditions and enduring human questions.