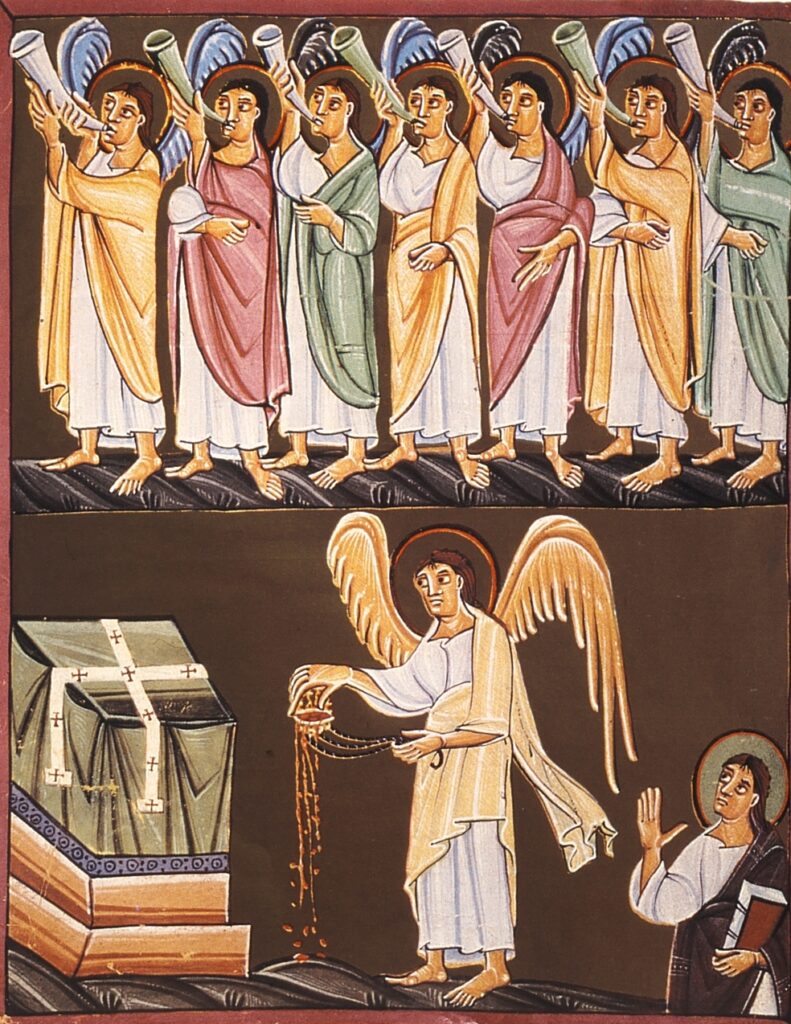

Featured image: The Beast of the Sea, Bamberg Apocalypse. John the Apostle, scriptorium at Reichenau. Bamberg State Library, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Key Takeaways

- Rich Symbolism: The Book of Revelation uses vivid imagery and metaphors to convey profound theological truths.

- Themes of Judgment and Hope: It juxtaposes divine justice with promises of redemption and restoration.

- Cosmic Conflict: Revelation portrays the ultimate triumph of good over evil through Christ’s victory.

- Historical and Cultural Influence: Its interpretations have evolved, shaping theology, art, and literature throughout history.

- Contemporary Relevance: Revelation continues to inspire hope, moral vigilance, and reflections on justice in modern times.

The Book of Revelation stands as the last text in the New Testament. Over the centuries, it has inspired diverse interpretations because of its striking symbols, apocalyptic visions, and intricate narratives. Written in a turbulent period for early Christian communities, it blends themes of cosmic conflict and eventual triumph. Readers encounter dramatic images of beasts, plagues, angelic proclamations, and a majestic vision of a new creation, all woven together through vivid language and layered meanings.

Often called the Apocalypse of John, Revelation was composed during the late first century CE—an era fraught with political unrest and spiritual challenges. Many in early Christian circles faced persecution from the Roman state, prompting theological reflections on divine justice and hope. Drawing on earlier Jewish apocalyptic traditions, Revelation proposes that despite earthly hardships, a transcendent plan stands behind historical events. This plan involves both judgment against oppressive powers and the promise of restoration for those who persevere.

This article looks at the Book of Revelation from a cultural, historical, and literary perspective. The goal is to shed light on its origins, symbolism, and the many ways it has been understood through the centuries. By tracing its interpretative history and examining how its imagery continues to resonate in modern culture, readers can better grasp why Revelation remains a fascinating component of Christian Mythology.

Table of Contents

Historical Context

Authorship and Exile

The Book of Revelation identifies its author as John, exiled on the island of Patmos “because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (Revelation 1:9). While tradition has often linked this John to the Apostle John—credited with writing the Gospel of John and the Johannine Epistles—scholars debate the precise identity of the text’s composer. The language, style, and theological emphases differ from the Gospel of John, prompting the idea that Revelation may be the work of a different individual who shared the same name or belonged to a Johannine community.

This exile likely occurred during the reign of Emperor Domitian (81–96 CE). Historical records suggest Domitian was zealous about securing loyalty through imperial worship, a practice that early Christians often found incompatible with their beliefs. Those who refused to worship the emperor faced punishment, marginalization, or worse. Under these conditions, Revelation takes the shape of an urgent pastoral message aimed at seven churches in Asia Minor.

Seven Churches in Asia Minor

The text addresses seven communities in Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea (Revelation 2–3). These congregations contended with various internal and external pressures, including competing teachings, threats of persecution, and cultural tensions. By mentioning real cities of that era, Revelation situates its theological visions in a tangible setting. It is not an abstract writing disconnected from reality; rather, it serves as an admonition and a source of encouragement for believers tested by adversity.

Roman Domination and Apocalyptic Literature

Revelation emerged in a broader cultural environment shaped by Roman rule. The empire’s political power extended across Europe, North Africa, and parts of Asia, with the imperial cult at its center. Cities built temples and hosted festivals to honor the emperor, underscoring Roman authority and uniting diverse populations. Christians who refused to participate in rituals venerating the emperor often found themselves in direct conflict with local authorities or neighbors who viewed them with suspicion.

Apocalyptic writings like Revelation thrived in such climates of social and political tension. Influenced by Hebrew prophetic traditions and texts such as the Book of Daniel, Revelation adopts a style that uses visions, angels, and cosmic battles to convey deep truths. It frames historical events within a larger spiritual narrative, asserting that oppressive forces will face judgment. This kind of literature reassured persecuted communities that their suffering was neither random nor permanent. Instead, it was part of a broader divine plan that would ultimately vindicate them.

The Destruction of the Second Temple

Another momentous event that shaped Christian and Jewish thought in that period was the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. Jewish hopes for divine intervention ran high, and many early Christians interpreted these events as signs that God’s plan was unfolding. The Book of Revelation, though written some years after the Temple’s destruction, draws upon and reworks biblical images in ways that reflect widespread eschatological expectations.

Key Symbolic Elements

Revelation teems with images that stir the imagination. These motifs—numbers, creatures, cosmic events—serve as vehicles for communicating profound ideas about justice, faithfulness, and ultimate destiny. Each detail is ripe for layered interpretations, weaving together themes that bridge the text’s ancient context with enduring questions about morality and the nature of power.

Numerology and the Number Seven

One of Revelation’s most prominent features is numerological symbolism, especially the recurrence of seven. This number is widely seen in biblical literature to represent completeness or divine perfection. Revelation references seven churches, seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven bowls of wrath. This repeated structure shapes the text, giving readers a sense of cyclical completion and highlighting the overarching coordination of events under divine oversight.

The significance of the number seven is not limited to any single passage; it punctuates the entire narrative. By presenting these sets of seven, Revelation underscores that the unfolding plan—whether it involves judgment, redemption, or renewal—reflects a comprehensive vision that includes every aspect of the cosmos.

The Throne Room and the Lamb

In Revelation chapters 4 and 5, John shares a vision of the heavenly throne room. This scene features God’s throne, surrounded by celestial beings who offer continuous praise. The central figure in this drama is the Lamb, a reference to Christ, described as “standing, though it had been slain” (Revelation 5:6). This seemingly paradoxical image encapsulates key Christian concepts: victory achieved through self-giving sacrifice, power manifest in humility, and triumph over evil secured by moral integrity rather than coercion.

Surrounding the throne are the four living creatures—often linked to all corners of creation—and 24 elders who represent the collective people of God. Their ceaseless worship underscores an affirmation that the ultimate authority belongs to the Creator. The entire scene invites readers to shift focus away from imperial might or societal pressures, directing awe and devotion to a higher sovereignty.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Revelation 6 reveals the famous Four Horsemen: riders on white, red, black, and pale horses. Their presence signals calamity unfolding on the earth. The first horseman may represent conquest, while the others bring war, famine, and death. Interpreters across time have assigned various meanings to these riders, sometimes tying them to specific historical periods, sometimes viewing them as archetypes of human suffering. They have been portrayed in art, literature, and media as agents warning that injustice and destructive tendencies eventually lead to crisis.

The concept of the Four Horsemen speaks to people in any era who witness social upheavals and catastrophes. Their iconic status stems from the simple yet stark imagery of impending doom, making them potent symbols for reflecting on collective responsibility and the fragility of human life.

The Woman, the Dragon, and the Beast

Chapters 12 and 13 of Revelation introduce another set of dramatic symbols. A radiant woman, often thought to represent the community of faith (or at times Mary, the mother of Jesus, or the people of Israel), is threatened by a dragon identified with Satan. The epic struggle that unfolds reflects a cosmic battle between good and evil, with the woman ultimately protected by divine intervention.

Revelation 13 introduces a beast arising from the sea, a figure widely interpreted as a representation of oppressive political forces. Its number, 666, has been the subject of constant scrutiny. Some scholars connect this number to Emperor Nero through numerical values of the letters in his name, while others interpret it as a general emblem of imperfection that falls short of divine completeness (often associated with seven).

Babylon the Great

Another evocative symbol is “Babylon the Great,” described as a grand city marked by wealth but mired in corruption. Babylon alludes to the ancient empire that once subjugated the people of Israel but, in Revelation, becomes an emblem of moral decay and oppression. Many interpreters over the centuries have read Babylon as a coded reference to Rome, whose persecutory practices were fresh in the minds of the early audience. Others extend the label to various exploitative systems, whether political or economic, that resist virtues like justice and compassion.

The New Jerusalem

In Revelation 21–22, readers encounter a culminating scene: the New Jerusalem descending from heaven. This city possesses walls, gates, and foundations, all described with splendor. The gates bear the names of Israel’s twelve tribes, while the foundation stones honor the apostles, symbolizing the union of Israel’s heritage with the Christian movement’s origins. The New Jerusalem is depicted as a place without a temple, because God’s presence permeates the entire city. Here, death, pain, and sorrow find no foothold—a perfect realization of redemption and unity.

This vision stands in contrast to the earlier horrors of plagues and destruction. It highlights the theological message that destruction paves the path for renewal. In biblical literature, chaos can precede an era of harmony, echoing prophetic works that predict a re-creation of the earth.

Changing Interpretations Through the Centuries

The Book of Revelation has spurred an array of interpretations that mirror evolving historical settings, theological trends, and cultural needs. Although some traditions treat Revelation as a direct prophecy of events to come, others see it primarily as a coded depiction of the early Christian community’s struggles under Roman rule. Many interpretive approaches exist, showing the book’s remarkable adaptability across time.

Early Church Perspectives

Leaders of the early church embraced Revelation as a source of assurance during oppression. Figures like Irenaeus (2nd century) took a more literal approach, holding that the text forecasted final events in the near future, with its admonitions applying to the moral and spiritual conduct of Christians under duress. Tertullian likewise cited Revelation to affirm that believers would witness a future resurrection and reign with Christ.

Allegorical readings also emerged. The cosmic battles in the text were viewed as representations of the Church’s struggles against hostile forces, both spiritual and earthly. Instead of predicting a series of external events, these thinkers emphasized an interior battle: the text symbolized the triumph of faithfulness amid corruption.

Medieval Interpretations

In the medieval era, Revelation loomed large in liturgical practices, sermons, and artistic expressions. Manuscripts and medieval art frequently portrayed the Four Horsemen, the harlot on the beast, and the final judgment, reflecting an age concerned about moral accountability and the afterlife. It was not unusual for interpreters to connect Revelation’s images to contemporary political developments, seeing them as signs that the end was nigh or that corrupt institutions would soon face divine wrath.

Notable medieval works, such as Dante Alighieri’s writings, while not direct expositions of Revelation, were shaped by its apocalyptic worldview. The persistent theme was the moral imperative to strive for spiritual purity. The text was also employed to highlight the inevitability of divine justice, urging individuals to ready themselves for the events it described.

Reformation and Confessional Debates

During the Reformation, Revelation became a tool in religious debates. Some Protestant reformers looked to it to criticize perceived abuses in the Roman Church, identifying the papacy with the beast or Babylon the Great. Martin Luther initially expressed reservations about including Revelation in the biblical canon, but he later recognized its usefulness in reflecting on the nature of evil. John Calvin chose to write extensive commentaries on many parts of the Bible but did not compose a full commentary on Revelation, possibly reflecting the text’s complexity and frequent use in polemical arguments.

Catholics, for their part, defended their own positions by offering alternative interpretations. Each side pointed to Revelation’s depictions of false prophets, judgments, and calls for repentance to argue that they were the true inheritors of Christian integrity. This tug-of-war reinforced the text’s significance in shaping religious identity.

Modern Readings: From Literal to Symbolic

In modern periods, Revelation has been interpreted in multiple ways, shaped by events like world wars, emerging nation-states, and changing views on eschatology. A few main interpretative stances have crystallized:

- Pre-millennialism: Holds that Revelation predicts specific future events involving a Great Tribulation and a literal millennium (1,000-year reign of Christ on earth). This perspective has been influential in certain evangelical contexts, producing extensive speculation about signs of the end times.

- Post-millennialism: Views the millennium not as an entirely future event, but as an era during which Christian ethics spread. This approach envisions society progressively shaped by Christian teachings before Christ’s final return.

- Amillennialism: Interprets the millennium in more symbolic terms, regarding it as the ongoing period of spiritual triumph since Christ’s death and resurrection. For these interpreters, Revelation’s events span both past and present, with no single future cataclysmic timeline.

Revelation also has a presence in popular culture. Novels such as The Late Great Planet Earth by Hal Lindsey or the Left Behind series by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins draw heavily on pre-millennialist ideas, connecting biblical prophecy to modern global crises. Films and television programs frequently mine Revelation’s motifs—plagues, anti-heroes, cosmic battles—for dramatic effect. These works reflect ongoing fascination with how an apocalyptic vision might apply to contemporary questions of morality and meaning.

Major Themes and Literary Dynamics

Judgment and Restoration

At the core of Revelation lies an unflinching portrayal of divine judgment on oppressive powers. The text describes calamities—earthquakes, blazing stars, and scorching heat—that express God’s direct response to persistent injustices and rebellions. In parallel, it proclaims a renewed creation where “death shall be no more” (Revelation 21:4). This interplay between wrath and comfort provides a moral framework: wrongdoing will not go unanswered, yet the chance for redemption remains open to those who persist in faith.

Cosmic Struggle Between Good and Evil

Revelation positions human history within a cosmic struggle. The Lamb stands for redemptive love and truth, while the dragon and various beasts signify manipulation, violence, and destructive ambition. These forces clash through the text, culminating in the ultimate defeat of evil (Revelation 20). By presenting the conflict on both earthly and heavenly stages, the narrative challenges readers to consider unseen dimensions of ethical and spiritual battles.

Witness and Perseverance

Throughout the book, an unwavering witness emerges as a virtue. Individuals who stand firm in belief, even under threat or persecution, play a vital role in Revelation’s scenarios. The martyrs—depicted under the altar in Revelation 6:9–11—ask for justice and are promised vindication. Their example testifies that faithfulness can shape events and that unwavering commitment can bring about transformation, even if the world’s powers seem overwhelming.

Worship and Allegiance

Revelation devotes significant space to scenes of worship (Revelation 4–5), contrasted with idolatry (Revelation 13). Who is worthy of worship, and which loyalties matter most, becomes a central question. The heavenly worship gatherings reinforce that ultimate sovereignty resides in the divine realm, not in human rulers. Readers find a pointed call to stay aligned with what is life-giving rather than yield to influences that distort or oppress.

Contemporary Relevance

Hope in a Time of Anxiety

In an era marked by environmental concerns, social inequalities, and political uncertainties, Revelation’s vision of renewal can resonate with those seeking assurance that injustice and suffering do not rule forever. Its powerful imagery of the New Jerusalem—where the tears of humanity are wiped away—continues to supply a glimpse of a more harmonious possibility.

Moral Challenge and Self-Reflection

Revelation’s critiques of complacent or compromised congregations (Ephesus, Sardis, Laodicea) highlight the danger of spiritual apathy. That warning extends to modern communities and individuals who might sacrifice genuine conviction for social acceptance or personal gain. By examining the errors of these early churches, readers can reflect on current practices and values.

Influence on Popular Culture and Art

Revelation’s dramatic visuals remain a wellspring for artistic and cultural expressions. Painters like Albrecht Dürer famously depicted scenes from Revelation, capturing its intensity and grandeur. Contemporary novels, graphic novels, and films turn to it for plot devices involving apocalypse and redemption. Musicians reference “Babylon” or the “Four Horsemen,” tapping into its potent sense of cosmic drama. Even secular audiences—while not embracing its theological claims—find its imagery compelling as a lens through which to contemplate endings, judgment, and rebirth.

Calls for Social Justice

Many interpret Babylon the Great (Revelation 17–18) as a stand-in for systemic injustice, prompting reflection on economic exploitation, political corruption, and moral irresponsibility. Activists and theologians have used these passages to inspire movements for social reform, seeing Revelation’s portrayal of Babylon’s downfall as proof that societies built on cruelty and inequality must eventually yield to justice and compassion.

Artistic and Scholarly Engagement

Visual and Liturgical Traditions

From the earliest days, Revelation inspired iconographic representations. Byzantine and medieval churches incorporated apocalyptic imagery in mosaics and frescoes. Illuminated manuscripts from the Middle Ages are filled with depictions of heavenly worship, the Lamb, the final judgment, and more. These artistic efforts gave life to the text, helping largely illiterate congregations visualize its teachings.

Liturgically, certain Christian traditions read Revelation’s visions of worship during services to evoke a sense of heavenly praise. Passages describing the Lamb’s victory or scenes of adoration can deepen the spiritual experience, reminding congregations of their connection to a cosmic chorus.

Modern Scholarship and Discourse

Modern scholarship tends to emphasize Revelation’s roots in first-century historical conditions. By comparing its symbols with those found in other Jewish and Greco-Roman writings, researchers illuminate how the text draws from established literary traditions. Some highlight parallels with political satire, suggesting that Revelation offers a coded critique of Roman power.

Literary and cultural studies scholars also investigate how Revelation’s apocalyptic worldview influences broader Western thinking about time, destiny, and the role of divine justice. These academic explorations—drawing from anthropology, history, and literary criticism—underline that Revelation is both a historical artifact and a living text with ongoing cultural ramifications.

Controversies and Debates

Revelation has sparked its share of controversies. Some early Christian communities questioned its place in the biblical canon, uncomfortable with its apocalyptic tone. Later critics objected to the violent imagery, concerned about how it might feed extremist outlooks. Indeed, across history, individuals have cited Revelation to predict the end of the world on specific dates or to justify destructive actions. These tendencies have led many theologians and clergy to caution against purely literal or sensational readings.

In interfaith dialogues, Revelation’s symbolism can be a source of misunderstanding or anxiety, particularly if interpreted as anti-Jewish or triumphalist. Balanced scholarly approaches recognize the Jewish origins of apocalyptic traditions and emphasize that Revelation critiques oppressive power structures rather than any single ethnic or cultural group.

Engaging with Revelation in Today’s World

Ongoing Significance for Literature and Media

Contemporary literature—ranging from science fiction to political thrillers—frequently borrows Revelation motifs. The “antichrist” figure, plagues reminiscent of the seven bowls, or a final cataclysm, can be reworked in modern narratives that address existential threats like nuclear war or pandemics. This reimagining shows how Revelation’s themes maintain a strong connection to human anxieties and hopes.

Film and television also capitalize on apocalyptic narratives. Audiences are drawn to stories where civilization teeters on the edge, reflecting an enduring fascination with endings and new beginnings. Revelation’s imagery, with angels battling dragons or cities falling in a single hour, stands out as a compelling blueprint for such tales.

Bridging the Ancient and the Present

While Revelation was shaped by Roman-era politics and concerns, it speaks to broader ideas about justice, faithfulness, and the ultimate reconciliation of creation. Its layered symbols remind readers that oppression is not everlasting and that perseverance holds value. The Book of Revelation invites a reflective mindset: it is both a product of its time and a mirror for subsequent generations to see their own struggles and aspirations in its pages.

Interdisciplinary approaches to Revelation—such as analyzing its influences on art, exploring its historical environment, or studying its linguistic patterns—can deepen contemporary understanding. By placing the text within conversations about politics, literature, ethics, and social responsibility, readers begin to see it as part of a complex cultural tapestry.

Reflecting on Hope and Responsibility

Revelation’s conclusion highlights hope: a holy city where tears cease and all brokenness finds healing. This picture of unity calls individuals to imagine a future shaped by compassion, moral integrity, and commitment to the common good. In times when fear or despair might dominate global discourse, Revelation’s final chapters offer an alternative outlook rooted in restoration.

Yet the text also asks for responsibility. The letters to the seven churches reveal flaws like indifference, immorality, and hypocrisy. Faced with a call to “remember from where you have fallen; repent,” believers today can draw parallels in personal or societal contexts. Regardless of one’s stance on literal end-time predictions, Revelation’s moral framework challenges complacency and stands against the notion that believers should passively wait for a distant event. The text signals that how communities live now matters.

Conclusion

The Book of Revelation commands attention through its apocalyptic language, bold images, and deep themes. Written in a period when the early Christian movement faced intimidation and danger, it fuses assurance with admonition. It offers sweeping visions of cosmic battles, the rise and fall of empires, and the ultimate restoration of the world.

Its pages remind readers that evil, no matter how imposing, is not lasting. The Lamb who was slain emerges victorious, highlighting an unexpected truth: genuine power may be expressed through love and sacrifice rather than force and domination. This paradox offers a source of reflection for individuals wrestling with the complexities of human existence.

Revelation also underscores the gravity of human choices. It calls communities to examine their loyalties, be vigilant against hypocrisy, and uphold integrity. The imagery of beasts and dragons may seem distant or archaic, yet it still resonates whenever tyranny and greed appear in modern life. Whether reading Revelation for historical interest, literary appreciation, or spiritual insights, one is confronted with a text that demands active engagement.

Across two thousand years of Christian tradition, Revelation continues to shape moral imagination, ethical outlook, and cultural creativity. It reminds humanity that beginnings and endings intersect in surprising ways. Despair can give way to hope, conflict can point to eventual harmony, and the anguish of the present can be transformed by the prospect of renewal. In a broad sense, the Book of Revelation stands as a rich testament to how mythic stories and symbols operate—bridging past and present, warning against wrongdoing, and beckoning readers toward an image of wholeness.