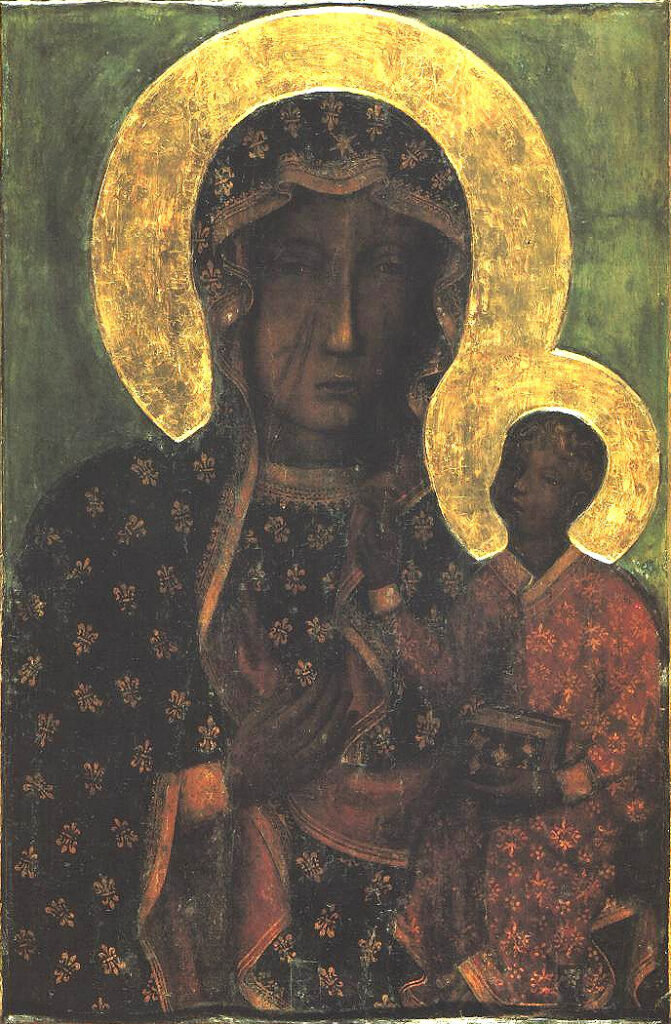

Featured image: the Black Madonna of Toulouse. Notre-Dame de la Daurade, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Key Takeaways

- Cultural Significance: The Black Madonna bridges ancient traditions and Christian symbolism, representing resilience and divine mystery.

- Global Presence: Found across Europe and beyond, Black Madonnas are central to diverse cultural and spiritual practices.

- Symbol of Suffering: Her dark skin often symbolizes shared human pain and the hope of redemption.

- Empowerment and Inclusivity: She inspires feminist, liberation, and eco-theological movements, celebrating diversity and empowerment.

- Timeless Relevance: The Black Madonna continues to resonate in art, theology, and popular culture as a universal icon of transformation.

The Black Madonna remains a compelling figure in Christian tradition, an icon that sparks devotion and reflection across continents and centuries. Depicting the Virgin Mary with dark or black skin, these images appear in chapels, cathedrals, and remote shrines worldwide and have long inspired reverence and pilgrimage. Although their beginnings often lie in obscurity, Black Madonnas have accumulated layers of meaning—spanning history, theology, and art—that point to a profound and enduring spiritual significance.

Far from being a mere artistic curiosity, the Black Madonna stands at the crossroads of multiple cultural legacies, at times reflecting the imprint of ancient goddess worship and, at other points, embodying the depth of Christian mysticism. Whether visitors encounter her in Montserrat’s rugged mountains or in Poland’s Jasna Góra Monastery, this figure sparks questions about resilience, maternal solace, and the expansive nature of divine compassion. The following sections explore how Black Madonnas arose in Christian iconography, what spiritual values they represent, and why they continue to captivate believers and seekers alike.

Table of Contents

Historical and Cultural Origins

Early Depictions of the Madonna

The Virgin Mary was a notable subject in Christian art from the faith’s earliest centuries. In Roman imperial times, artists often rendered her as a tender mother holding the Christ Child, highlighting purity, holiness, and divine motherhood. Over the centuries, images of Mary multiplied throughout Europe. The Middle Ages, in particular, saw diverse regional expressions, each reflecting local theological emphases and artistic styles.

Within this proliferation of Marian artwork, the Black Madonna began to stand out as a distinct phenomenon. While most Marian images featured fair-skinned depictions, certain paintings and statues portrayed Mary with dark or black skin. Many originated in medieval Europe, yet their exact beginnings are frequently mysterious, with some legends suggesting they predate Christianity itself. The broad presence of these statues and images in France, Spain, Italy, Eastern Europe, and beyond underscores their combined religious and cultural value.

Interpreting Dark Skin in Early Christianity

A range of theories has been proposed to explain why certain Marian artworks emphasize dark or black skin. Some scholars identify a continuity with ancient traditions, noting that revered female figures in various cultures were shown with dark skin to signify fertility, wisdom, or the nourishing qualities of the earth. Comparisons to the Egyptian goddess Isis—often depicted as a dark-skinned mother bearing the child Horus—demonstrate how these pre-Christian motifs might have shaped medieval religious art.

Other explanations focus on material and environmental factors. Over the centuries, exposure to soot from candles and incense or changes in paint pigments could darken statues or paintings. However, the idea that all Black Madonnas arose by chance seems insufficient, especially for artworks deliberately created with dark pigmentation. In Christian symbolism, black was at times associated with divine mystery, humility, and the inexplicable aspects of God’s wisdom—suggesting that some artists may have chosen this coloration to highlight theological truths.

Geographic Spread and Renowned Examples

Most commonly, Black Madonnas have been venerated in regions with a deep Catholic heritage. Many carry local stories of miracles or special protection, which increases their spiritual prestige. One of the most revered is Our Lady of Czestochowa in Poland, whose devotees often refer to her as the “Queen of Poland.” Believers credit her with miraculous interventions, including safeguarding the country against invading forces. Another well-known example is the Black Madonna of Montserrat in Catalonia, affectionately called “La Moreneta.” Enshrined high in the mountains, she has drawn pilgrims for centuries, many believing her image channels healing and divine aid.

Similar devotions arise at sites like the Black Madonna of Einsiedeln in Switzerland or the Virgin of Guadalupe in Spain’s Extremadura. Even though most Black Madonnas are closely linked to Europe, their reverence extends beyond. In the Americas, the figure of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico, while distinct in origin and style, shares thematic and visual resonances with Black Madonnas, thus embodying an inclusive vision that merges Indigenous heritage with Catholic devotion.

Through these examples, it becomes evident that Black Madonnas surpass their local contexts, standing as global manifestations of faith and cultural synthesis. Their origins might involve ancient worship, creative symbolism, or the meeting of multiple religious threads, but their enduring impact shows the universal power of sacred art to attract and unify people.

Theological Interpretations

Emblem of Suffering and Endurance

In Christian tradition, the Black Madonna often symbolizes both suffering and resilience, mirroring Mary’s profound sorrow as she watched her son’s crucifixion. When Mary’s image is rendered with dark skin, some interpreters view this as a reflection of humanity’s pain, particularly that of those who are marginalized or oppressed. She becomes a compassionate ally, offering solace to all who endure hardship.

In this sense, the Black Madonna speaks to universal vulnerability. Her presence conveys that divine mercy extends into even the darkest corners of human experience. People in dire circumstances—whether due to poverty, discrimination, or personal loss—may identify with a Madonna whose portrayal reflects themes of tribulation and unwavering hope. Theologically, she represents the belief that God accompanies the suffering, turning anguish into the promise of redemption.

Maternal Figure and the Feminine Archetype

The Virgin Mary already epitomizes a mother’s care and comfort in Christian teaching, and the Black Madonna accentuates this aspect in a powerful way. Her dark appearance echoes symbols of the fertile earth in ancient spiritualities, evoking nourishment and protection. This connection underscores continuity between Christian devotion and pre-Christian feminine archetypes such as Isis or Cybele, both seen as great mother figures in their respective traditions.

Such parallels reveal that feminine imagery in religion did not vanish with Christianity’s rise but found new expressions under Marian devotion. The Black Madonna stands at this intersection, bridging different conceptions of the maternal divine. For many modern believers, she personifies not only tenderness but also the fortitude and endurance often demanded by life’s hardships, offering women in particular a strong role model of spiritual depth and transformative power.

Mystical Dimensions and Allegorical Meaning

In Christian mysticism, darkness has frequently symbolized God’s inscrutability—an invitation to contemplation and faith rather than an indication of evil. The Black Madonna’s dark features can point toward the hidden facets of divinity that elude human comprehension. She serves as an artistic embodiment of the belief that God’s profound wisdom often surfaces only after a period of struggle or obscurity.

Additionally, alchemical metaphors that were influential in medieval Christian thought connect blackness with the nigredo phase of inner transformation, a stage of dissolution that precedes renewal. Within this framework, the Black Madonna can be seen as a spiritual companion guiding believers through trials toward illumination. Her depiction also resonates with a more inclusive picture of the sacred, expanding notions of who is represented in holy images and highlighting the unity of all people before God’s love.

Veneration and Pilgrimage

Historical Devotional Practices

Devotion to the Black Madonna is well documented in Christian history, especially in medieval Europe. Many shrines dedicated to her became prominent pilgrimage destinations, where stories of miracles—ranging from healings to communal protection—intensified her revered status. Among the earliest centers of such devotion is the Jasna Góra Monastery in Poland, safeguarding Our Lady of Czestochowa, whose interventions were credited with warding off foreign invasions. Another example is Montserrat in Spain, where pilgrims have traveled for centuries to seek the assistance of “La Moreneta,” in hopes of experiencing recovery from illness or finding spiritual renewal.

Liturgical celebrations often evolved around these icons. Special feast days and processions underscored the Madonna’s protective nature. In France, for instance, Our Lady of Rocamadour’s feast involved candlelit gatherings and blessings for travelers, emphasizing her reputation as a guardian.

Modern Pilgrimage and Diverse Expressions of Faith

Contemporary devotion to the Black Madonna persists, drawing Catholics and non-Catholics alike to ancient sanctuaries. Sites like Montserrat still host large numbers of visitors, many climbing the challenging trails to approach the statue for contemplation, prayer, or cultural exploration. In Poland, millions visit Czestochowa each year, reflecting the ongoing reverence for the so-called “Queen of Poland,” whose feast day includes vibrant liturgical services.

Beyond these traditional Catholic observances, the Black Madonna also resonates with various spiritual movements outside official Church structures. People may encounter her as an icon of resilience, reconciliation, or the sacred feminine, inviting them to engage in retreats or meditative practices that emphasize healing and inner growth. Workshops that focus on the Black Madonna’s symbolism often concentrate on themes such as empowerment, communal solidarity, and tapping into a broader understanding of divinity.

Syncretism in Broader Religious Contexts

Over time, the Black Madonna has adapted to contexts outside her European roots, merging with indigenous and African-derived spiritual traditions in places like the Caribbean and Latin America. In Haitian Vodou, for instance, the Black Madonna is sometimes equated with Ezili Dantor, a figure of fierce maternal love and independence, particularly cherished by communities facing oppression. This blending exhibits how the Madonna’s symbolism overlaps with other motherly deities or protective spirits who share her qualities of compassion, strength, and guardianship.

Similarly, throughout Latin America, the revered Virgin of Guadalupe—while possessing her own historical and artistic lineage—functions in a role akin to that of the Black Madonna, bridging Indigenous identity and Catholic faith. Her darker complexion and association with pre-Hispanic symbolism echo the inclusive dynamic seen wherever Black Madonna icons appear, demonstrating how these revered images often serve as profound, unifying symbols of faith, merging different cultural elements into a singular source of devotion.

Iconography and Artistic Representations

Defining Elements of Black Madonna Imagery

Black Madonnas typically appear either in two-dimensional icons or in sculptures, most often showing the Virgin enthroned and supporting the Christ Child on her lap. Their skin tone is notably dark or black, sometimes accentuated by vibrant garments and the rich gold of halos or crowns. This contrast with the more familiar fair-skinned Marian images imbues the Black Madonna with a unique aura. While certain representations are austere and rustic, underscoring humility, others feature elaborate finery, reflecting the resources and devotion of sponsoring communities.

The Christ Child is commonly shown making a gesture of blessing or holding a small orb or book, signifying his messianic and teaching roles. Adornments like jeweled crowns, embroidered robes, or floral motifs add to the sense of regal dignity. Given the centuries-long history of veneration, these icons often undergo refurbishments, and their aesthetic details may shift over time. Nonetheless, the unifying characteristic remains Mary’s dark visage, which anchors a distinctive spiritual identity.

Impact on European and Global Art

Throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the Black Madonna’s presence influenced Western religious art, prompting commissions for churches, abbeys, and royal chapels. Her image was not seen merely as decoration but as an object of worship and an essential part of liturgical life. The famed Lady of Czestochowa, with her dark features and scars, has been reproduced innumerable times, attesting to the deep attachment believers feel for her. Montserrat’s statue, likewise, became a model for Marian art, replicated wherever devotion to that particular shrine spread.

In modern times, contemporary artists, playwrights, and writers continue to invoke the Black Madonna’s image. Some reinterpret her to address social questions like racial equality or the role of women in religious settings. Others emphasize her mystical dimension, producing multimedia installations that incorporate both traditional religious motifs and modern creative elements. For many, she symbolizes an enduring heritage that transcends doctrinal boundaries, inviting exploration of spiritual, cultural, and aesthetic realms.

Iconography in Non-European Settings

Outside Europe, similar representations of dark-skinned Madonnas often incorporate local cultural idioms. In parts of Latin America, the Virgin’s depiction reflects Indigenous features, connecting her more directly to the ancestral heritage of the region. Even if not formally labeled as “Black Madonnas,” these images frequently share thematic parallels: they represent divine motherhood, compassion, and solidarity with marginalized communities. In Africa and parts of the Caribbean, where Christianity integrated with local spiritual practices, depictions of Mary with dark skin can blend Christian and ancestral aesthetics, further amplifying her meaning as a unifying maternal figure.

Through such artistic confluence, the Black Madonna traverses artistic genres and geographic boundaries. Her ever-evolving portrayal underscores her adaptability—she resonates with each cultural setting’s hopes, struggles, and deepest spiritual yearnings.

The Black Madonna in Contemporary Thought

Feminist and Liberation Theology

In modern theology, the Black Madonna has emerged as a potent emblem within feminist and liberation-minded discourses. Feminist theologians highlight her as a positive image of the divine feminine, challenging patriarchal interpretations of Christian doctrine. By representing fortitude, nurturing love, and endurance in the face of suffering, she offers a perspective that accentuates the importance of women’s experiences and spiritual power.

Liberation theologians, especially those in Latin America and other regions grappling with social inequities, emphasize the Black Madonna’s role as an ally of the poor and marginalized. Her dark skin often carries connotations of shared hardship, offering a source of hope and a call to social engagement. Rather than simply being an object of reverence, she can function as a rallying symbol for those working toward justice and dignity for the oppressed, revealing a God who stands on the side of the downtrodden.

Cultural and Spiritual Revival

Interest in the Black Madonna has expanded well beyond official ecclesiastical circles. Modern seekers of all backgrounds find in her a connection to earth-centered spirituality, ancient wisdom, and an inclusive portrayal of holiness. Many turn to her in times of personal crisis or transition, seeing her as a guide toward wholeness and a compassionate presence who understands life’s challenges. Retreats or conferences centered around the Black Madonna often focus on inner healing, empowerment, or reconnection with nature and community.

This resurgence is also evident in the arts and popular culture. Musicians, poets, and novelists draw upon her mystique to explore identity, resilience, and the dynamic between tradition and innovation. From paintings and digital media to performance pieces, creators find in the Black Madonna an image that transcends religious boundaries, bridging diverse experiences and worldviews. She is invoked to champion the forgotten, give voice to cultural hybridity, and provoke reflection on what it means to embrace both tradition and change.

Popular Culture and Modern Adaptations

The Black Madonna’s visibility in popular culture has grown, whether through songs that reference her symbolic depth or films that highlight her presence as a sign of grace and healing. In some works, she appears as an otherworldly figure who influences characters’ journeys toward self-discovery or reconciliation. In others, she stands for cultural pride and resistance against long-standing stereotypes, reinforcing the notion that sanctity can dwell in varied forms.

Such portrayals bring her into contact with audiences that might never step inside a pilgrimage church. This broadened exposure can spark curiosity about her history and theology, inspiring deeper exploration into the traditions that have honored her for centuries. It also enriches discussions about spirituality, heritage, and community in an increasingly pluralistic world.

Conclusion

The Black Madonna is a powerful presence in Christian tradition and beyond, bridging antiquity with current cultural consciousness. Her dark-skinned portrayal offers a rich tapestry of meanings: she embodies comfort for those in pain, offers a maternal tenderness that transcends cultural barriers, and invites reflection on the divine mystery that often lies beneath the surface of ordinary human life.

Tracing her origins reveals how early Christian art mingled with older religious influences, underscoring humanity’s persistent quest to depict a nurturing, protective deity. As a manifestation of the Virgin Mary, she incorporates themes of fertility, suffering, and maternal care, reminding the faithful that the sacred includes the marginalized and the misunderstood. Over the centuries, devout pilgrims have flocked to her statues and paintings, seeking miracles or solace from her watchful gaze.

Today, her significance endures and evolves. Whether invoked in feminist theology, celebrated in vibrant processions, or contemplated for personal spiritual growth, the Black Madonna remains a living symbol of resilience and inclusive grace. Her darker complexion challenges narrow conceptions of sanctity, illustrating a more expansive view of the sacred that crosses racial, cultural, and societal boundaries. Through the centuries, she has stood as a beacon for communities needing healing, unity, and hope, and her story is far from concluding.

Regardless of one’s religious alignment or cultural context, the Black Madonna’s universal themes—strength amid adversity, compassion for the vulnerable, and reverence for the divine feminine—continue to resonate. Her image speaks of a God who identifies with humanity’s struggles, welcomes diversity, and radiates love in forms that are at once mysterious and beautifully familiar. As new generations discover or rediscover her, the Black Madonna’s capacity to inspire remains a vivid and enduring testament to the richness of spiritual heritage.