In Catholic tradition, the opening chapters of the Book of Genesis offer us far more than a mere story about beginnings. They invite us into a mythic narrative—in the deepest sense of “myth”—that unveils divine truths about God, creation, and human destiny. Far from a fairy tale, Genesis is where we encounter the archetypal patterns of order emerging from chaos, of light dispelling darkness, and of a loving Creator actively shaping every dimension of reality.

For centuries, Catholic thinkers have recognized Genesis as a “lived myth”: a set of images and events that capture transcendent truths about our relationship with God. In the traditional Catholic framework, where the liturgy (including the Tridentine Mass) emphasizes reverence and continuity, these creation themes resonate powerfully. Each Mass in effect re-presents God’s primordial act of creation by offering thanks (Eucharist) for the new creation we receive in Christ.

Table of Contents

The Catholic Understanding of “Mythic” Creation

In common usage, the word “myth” can suggest fiction; yet, in a Catholic sense, myth points to stories that embody truths touching on the eternal. The Genesis account of creation is precisely such a narrative. As many traditional theologians observe, the Creation account reveals God as both transcendent and intimately engaged with His handiwork. The ancient forms, poetic repetitions (“And God saw that it was good…”), and symbolic structure (seven days) function to teach us—in both imaginative and didactic ways—how the cosmos is ordered and how human beings fit within that divine order.

Communities with a strong traditional orientation insist that we interpret Genesis in keeping with the patristic and medieval heritage. The early Church Fathers (e.g., St. Augustine, St. Basil) read the Creation account as factual in its essence yet rich in allegorical and spiritual applications. This approach holds together the historicity of God’s creative activity and the text’s deeper, timeless meaning—both of which shape our understanding of salvation history.

The Fall, Original Sin, and the Need for Redemption

Original Harmony

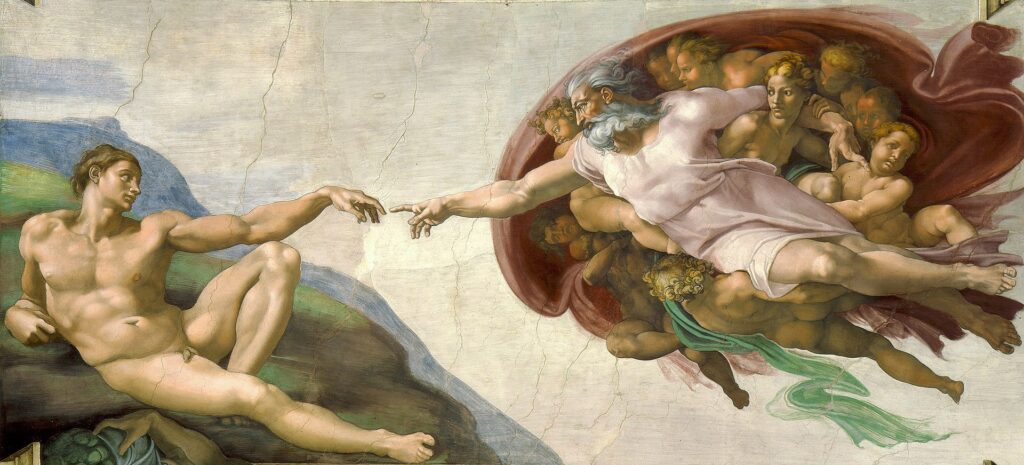

Genesis paints a vivid picture of God forming Adam from the dust, breathing life into him, and gifting him stewardship over creation. Eve, formed from Adam’s side, completes the primordial family. Symbolic or literal, the imagery conveys an original harmony among God, humanity, and the natural world. Eden is a paradise of communion—a blueprint for the relationship of trust, obedience, and intimacy we are all called to share with the Creator.

Fracturing Creation Through Sin

Yet the narrative swiftly shows a tragic rupture. Tempted by the serpent, Eve eats from the forbidden tree and shares the fruit with Adam. In that act of disobedience, often called the Original Sin, disorder permeates creation. Pain, toil, and mortality become the human condition. More deeply, sin alienates us from God, who is our true source of life. For St. Augustine, whose insights heavily influence Catholic thought, the Fall is not simply a cautionary tale but the reason the entire world “groans” awaiting redemption (cf. Romans 8:19–22).

The Necessity of Christ’s Redemptive Work

Here is where the Catholic faith proclaims a central truth: if all creation suffers under the weight of sin, then we need a Savior who can restore us to communion with God. Genesis paves the way for a messianic hope. The Church, especially in its older liturgical forms, underscores this interplay between sin and grace: we see it in the solemn petitions of the Mass and in the repeated prayer, “Lord, have mercy.” The drama of Genesis sets the stage for the ultimate rescue—Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross.

Creation as Foreshadowing the New Creation

Biblical Typology

Catholicism has always practiced typological reading of Scripture. Genesis contains countless figures and images that point ahead to Christ:

- Adam as Type of Christ: Adam’s disobedience dooms humanity; Christ’s obedience on the Cross redeems it.

- Garden Imagery: Eden, where sin begins, prefigures Gethsemane, where Christ confronts the weight of sin and prays, “Not my will, but yours be done.”

This “foreshadowing” style brings unity to both Old and New Testaments. Where the world once fell under the dominion of sin, it can now look toward a future “new heaven and new earth” (Revelation 21:1).

Liturgical Resonance

Each year, the Church’s liturgical cycles retell the story of our fall and restoration. At Easter, the Exsultet calls Adam’s sin a “felix culpa”—a happy fault—because it won for us so great a Redeemer. Even the structure of Mass—beginning with a penitential rite, culminating in the offering of the Lamb of God—mirrors the arc of creation, fall, and redemption. Such resonance is especially pronounced in the Tridentine Mass, which preserves an atmosphere of solemn reflection on humanity’s need for salvation and the immensity of God’s mercy.

Salvation History in the Great Catholic Tradition

Covenants Through the Ages

The Church teaches that salvation history unfolds through a series of covenants:

- Creation Covenant: God blesses Adam and Eve, establishing them as His children.

- Noahic Covenant: After the flood, a new promise arises that preludes a fuller restoration.

- Abrahamic Covenant: God calls Abraham to father a chosen people, from whom the Messiah would spring.

- Mosaic Covenant: The Israelites receive the Ten Commandments, shaping their moral and ritual life.

- Davidic Covenant: The promise of a king whose dynasty will last forever, pointing to Christ the King.

The underlying theme: God refuses to abandon His creation, continually inviting His people into deeper covenantal union. From the vantage of Catholic Tradition, every one of these steps clarifies the blueprint set forth in Eden and fulfilled in Christ.

Medieval Devotions and Scholastic Insights

In the medieval period, thinkers like St. Anselm and St. Thomas Aquinas reflected extensively on how “the Word made flesh” (John 1:14) restores the design shattered by Adam. Aquinas, following patristic sources, taught that the entire cosmos—physical and spiritual—finds unity in the person of Jesus, the Incarnate Word. Liturgical devotions, from Corpus Christi processions to chanting of the Divine Office, made creation’s order audible and visible, enabling the faithful to glimpse the Edenic harmony God intends.

Thus, the Christian view of cosmic redemption was so radical it shaped Western civilization’s moral compass in ways we often take for granted today. Compassion, dignity of all persons, and the notion that historical progress can align with moral truth all have biblical and patristic roots.

These longstanding beliefs about a created order and humanity’s redemption in Christ remain vigorously affirmed. The importance of continuity with the Church’s prior teachings ensures that the blueprint of creation—sin’s disruption, God’s covenants, and Christ’s redemptive mission—never becomes diluted by passing trends.

Christ the New Creation: Culmination of the Blueprint

Incarnation as a Second Genesis

When the Blessed Virgin Mary consents to the Angel Gabriel’s message, she effectively becomes the New Eve—where Eve doubted, Mary believes; where Eve disobeyed, Mary says “Fiat mihi” (“Let it be done to me”). This pivotal “yes” inaugurates a new creation in Christ. Born of the Virgin, He is the New Adam. St. Paul writes: “for as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ.” (1 Corinthians 15:22). This is no mere poetic flourish but the essence of the Christian claim: Jesus corrects and elevates the original blueprint of humanity.

Resurrection and Re-Creation

If the Incarnation is like a new beginning, then the Resurrection is the full blossoming. Sin, suffering, and death do not have the final word; instead, the empty tomb signifies that “all things are made new” (Revelation 21:5). At Easter, particularly in the Traditional Latin Mass, the faithful celebrate in a manner rich with ancient symbols—baptismal water, Easter fire, the Paschal candle—echoes of Genesis’s primordial light. We perceive our fallen nature being re-created. Eearly Christians’ proclamation of a crucified and risen Lord utterly reshaped cultural norms, planting the seeds of what we now see as universal human rights, care for the vulnerable, and hope in the midst of trials.

Eucharist: Ongoing New Creation

The Mass is where this new creation is renewed daily. As the bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Christ, we receive the same grace that overcame the rupture introduced in Genesis 3. The sense of awe that marks the Tridentine liturgy—its reverent gestures, the silent Canon, the repeated signs of the Cross—reflects the grandeur of the cosmic drama re-presented in every celebration: creation renewed and sanctified.

Practical Takeaways: Living the Creation Narrative Daily

- Liturgical Anchors

- Attend the Traditional Latin Mass (or a reverent vernacular Mass) to experience how the Church integrates Eden’s harmony into worship. The chant, incense, and silent reverence immerse the soul in the cosmic dimensions of redemption.

- Embrace the Church’s liturgical year: Advent and Easter Vigils are particularly rich in creation imagery—Advent begins in darkness, yearning for light; Easter triumphs with Christ’s victory over sin.

- Devotions and Prayer

- The Liturgy of the Hours: an ancient practice that structures prayer around sunrise, midday, sunset, and nightfall, echoing the creation cycles of day and night.

- The Rosary: called the “Bible on a String,” it meditates on the mysteries of Christ’s life, including the Joyful Mysteries that link Mary’s “yes” to the new creation, paralleling the dawn of Eden.

- Marian Consecration: fosters the sense that Mary, as the New Eve, gently reorients hearts away from the disorder introduced by sin and toward her Son’s redemptive grace.

- Ecological and Cultural Implications

- Recognize in the goodness of creation the seeds of a moral responsibility to care for the environment, seeing the natural world as a gift over which we are stewards, not absolute masters.

- Practice gratitude and hospitality, reflecting how God first made Adam and Eve recipients of a bountiful world.

- Family Catechesis

- Introduce children to the wonder and reverence for God’s creative acts—reading Genesis aloud, connecting it to Christian feasts, discussing moral lessons about temptation, obedience, and divine mercy.

- Encourage them to see everyday life—house chores, gardening, caring for animals—as cooperating with God’s ongoing project of creation.

Conclusion: Embracing Our Role in the Ongoing Creation

From its opening line—“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1)—Scripture beckons us to view our entire existence through a lens of divine purpose. The Creation narrative is more than an origin story; it is a blueprint for our salvation. The promise that God established in Eden still resonates in every Mass, every sacrament, and every moment we open our hearts to receive grace.

Through Christ, we are offered a second chance—indeed, a new creation. By rooting ourselves in the rich devotions and liturgical traditions that keep Genesis “alive” in our souls, we enter more deeply into that drama of salvation. We do not merely read about Eden’s fall; we confront our own fallenness. We do not merely lament Adam’s exile; we rejoice that the New Adam undoes sin’s penalty. And in every dimension of life—family, parish, culture—we can echo the psalmist’s song: “O Lord, how manifold are Your works! In wisdom have You made them all” (Psalm 104:24).

As we ponder the creation story, let us grasp its enduring power: we were made by Love, for love, and redeemed by the greatest act of love. May we live and worship accordingly, embracing both the awe and responsibility that come from seeing Creation as the first chapter in the eternal narrative of our salvation.