Featured image: Six-wiged Seraph by Vrubel. Shakko, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Key Takeaways

- Dual Origins: The Hebrew word “saraph” means both “fiery” and “serpent,” hinting at the seraphim’s ancient roots as supernatural serpentine figures.

- Isaiah’s Vision: In the Bible, seraphim appear only in Isaiah’s vision, depicted as six-winged beings who proclaim God’s holiness and perform acts of purification.

- Cultural Parallels: The concept of fiery, protective beings appears across ancient cultures, including Egyptian, Babylonian, and Near Eastern traditions.

- Monotheistic Evolution: As Israelite religion moved to monotheism, serpentine figures were reinterpreted as divine beings serving Yahweh.

- Role in Angelology: Christian thinkers like Pseudo-Dionysius and Aquinas elevated seraphim as the highest angelic order, symbolizing divine love and purity.

- Artistic Influence: In art, seraphim were depicted as fiery, radiant beings, often in red and orange to symbolize their burning devotion.

- Universal Archetype: Similar beings in Islamic, Hindu, and Zoroastrian traditions show that themes of fire, purification, and guardianship are universal.

Few figures in Christian and Jewish mythologies evoke as much fascination as the seraphim. These six-winged beings, described only once in the Hebrew Bible, appear in the Book of Isaiah, where they hover around God’s throne, crying out,

“Holy, holy, holy is Yahweh Sabaoth.

His glory fills the whole earth.”— Isaiah 6:3

Each seraph’s wings serve a purpose: two to cover their face in reverence, two to cover their feet in humility, and two for flight to act swiftly in service.

Though briefly mentioned, the seraphim have permeated Jewish and Christian thought for centuries, standing apart from other angels with an exalted role near God. Unlike angels who often serve as messengers, the seraphim act as guardians of divine holiness. But the origin of the seraphim’s name and form—derived from “saraph,” meaning fiery serpent—raises intriguing questions: were they once envisioned as supernatural serpents? Did they evolve from symbols of fire and serpents into angelic figures that symbolize divine love, purity, and God’s proximity? This article explores the seraphim’s journey from Near Eastern myth to their high place in theology, tracing their transformation and lasting influence.

Table of Contents

Etymology and Early Symbolism of “Seraphim”

The Hebrew term “saraph” offers insights into the seraphim’s early nature, containing meanings of both fire and serpent. In ancient cultures, these symbols held sacred power. Fire was divine, purifying and protective, while serpents symbolized fearsome power and supernatural qualities. The seraphim’s ambiguous nature combines these potent traits.

Seraphim as Fiery Serpents

- In Numbers and Deuteronomy, “saraph” refers to “fiery serpents” that plagued the Israelites, leading Moses to create a bronze serpent to heal the afflicted. This image of a dangerous yet revered serpent implies a pre-Israelite context where serpents symbolized both power and healing.

- Egyptian Parallels: Egypt’s uraeus symbol—portrayed as a cobra raised in a striking pose—was a powerful icon of protection, believed to spit fire at enemies. This blending of fire and serpent was likely familiar to early Israelites and may have shaped their understanding of the seraphim.

- Babylonian Influence: In Babylonian myth, fiery serpents served as intermediaries, and the fire-god Nergal manifested through flames and fiery beings, similar to later depictions of the seraphim as holy fire.

Divine Presence and Transformation

These symbols likely influenced Israelite views, leading to an understanding of the seraphim as beings of divine fire—both feared and revered. The seraphim in Isaiah represent the convergence of fire and serpent imagery, symbolizing a divine presence both powerful and purifying. In the Hebrew Bible, “seraph” serves as a complex archetype blending divine power with spiritual purification, establishing the seraphim as beings close to divine fire.

The Vision of Isaiah: Seraphim in the Hebrew Bible

Isaiah’s vision in chapter 6 marks the sole biblical description of seraphim, where they appear as fiery beings surrounding God’s throne, calling out a triple declaration of holiness—“Holy, holy, holy”—underscoring their role as guardians of God’s presence.

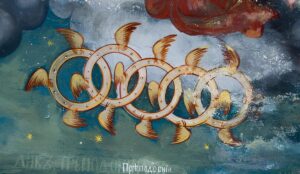

Symbolic Functions of the Seraphim’s Wings

The six wings of each seraph serve a specific symbolic function:

- Humility: Two wings cover their faces before God’s overwhelming glory.

- Reverence: Two wings cover their feet, possibly denoting a gesture of respect or vulnerability.

- Readiness: The final two wings are for flight, symbolizing their immediate response to God’s will.

In this vision, the seraphim also act as instruments of purification. One seraph uses a burning coal to cleanse Isaiah’s “unclean lips,” a moment that purges Isaiah’s sin and prepares him for prophecy. Here, the seraphim’s fire-filled nature embodies the divine power of transformation and purification, a theme that would deeply influence Jewish and Christian theology.

Distinguishing Seraphim from Cherubim

While cherubim in the Hebrew Bible act as protectors of sacred spaces, such as the Garden of Eden, the seraphim’s purpose is to remain close to God in perpetual adoration. They are not guardians of physical spaces but of divine holiness, with an “all-consuming passion for God” that aligns with their etymology and role as fiery, spiritual beings.

Seraphim as Serpentine Figures: Pre-Israelite and Early Israelite Traditions

Before they were angelic beings, the seraphim may have existed as fiery serpents in early Israelite traditions.

Serpents as Symbols of Power and Protection

- Ancient Near Eastern Symbolism: In Egyptian and Canaanite culture, serpents held associations with sovereignty, protection, and divine power.

- Hebrew Bible Connections: Numbers 21:4-9 recounts fiery serpents afflicting the Israelites, and the bronze serpent, later called Nehushtan, served as a healing symbol, highlighting the role of serpents in both punishment and redemption.

The Nehushtan, destroyed by King Hezekiah in an effort to eliminate idol worship, reflects a time when serpent worship may have coexisted with Yahweh worship. The fiery serpents were then transformed, eventually representing holy beings at Yahweh’s throne, shifting with the growth of monotheism in Israelite belief.

Transition from Fiery Serpents to Angelic Guardians: The Influence of Monotheism

As Israel moved toward monotheism, beings associated with Yahweh’s holiness were reinterpreted to align with a theology that emphasized a singular, supreme deity.

Purification and Transformation in Isaiah’s Vision

In Isaiah’s account, the seraphim purify Isaiah with a burning coal, acting as distinct and purposeful beings that serve God alone. This transformation from nature-linked symbols to divine attendants underscores how religious symbols were reshaped to reflect the monotheistic framework and the worship of Yahweh.

- Role within the Divine Court: Unlike other figures like Canaanite deities, seraphim were recast as attendants of God, existing to uphold Yahweh’s holiness.

- Jewish Angelology: Texts such as the Book of Enoch expanded on their role, presenting seraphim and cherubim together in God’s court, reinforcing a structured hierarchy and the seraphim’s unique association with fire.

The seraphim’s evolution from serpents to exalted beings illustrates the flexibility of religious symbols, reshaped to reflect purity, divine order, and monotheistic ideals.

Seraphim in Christian Angelology: From Isaiah to Aquinas

Christian theology further structured the seraphim as exalted angelic beings, drawing on their role in Isaiah’s vision but developing a more complex angelology.

The Celestial Hierarchy of Pseudo-Dionysius

- Fiery Essence: Pseudo-Dionysius, in De Coelesti Hierarchia, placed seraphim at the highest rank, viewing their fiery nature as symbolic of pure, consuming love for God.

- Divine Illumination: Their love radiates outwards, making them models of spiritual devotion and purity.

Thomas Aquinas and the “Excess of Charity”

Aquinas in Summa Theologiae described the seraphim’s love as a purifying, all-consuming fire, making them embodiments of divine charity. Their presence, for Aquinas, illustrated:

- Spiritual Purification: Their love served as a purifying force that drew beings closer to God.

- Symbol of Divine Grace: Their intensity made them ideal spiritual models for humanity, symbolizing divine illumination and grace.

The seraphim thus evolved as exalted beings in Christian thought, blending earlier Judaic imagery with new Christian interpretations.

Symbolism of Seraphim in Art, Literature, and Mysticism

The seraphim’s fiery, angelic imagery became a powerful symbol in art, literature, and mysticism, representing humanity’s highest spiritual aspirations.

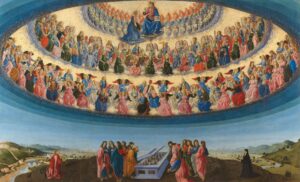

Artistic Depictions

- Renaissance Art: Artists like Giotto depicted the seraphim as fiery beings in works like St. Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata, merging the seraphim’s divine fire with human spiritual fervor.

- Symbol of Purity and Love: Their fiery wings and intense colors (reds, oranges) signified their holy devotion and purifying presence.

Literary and Mystical Interpretations

- Bonaventure and Spiritual Ascent: The wings symbolized stages on the soul’s path to God: humility, knowledge, and divine love.

- St. John of the Cross: In The Living Flame of Love, St. John used fiery imagery of the seraphim as a metaphor for divine love, illustrating spiritual purification and the soul’s union with God.

These depictions highlight the seraphim’s role in spiritual transformation, symbolizing the journey from earthly imperfection to heavenly unity.

Comparative Analysis: Seraphim and Similar Beings in Other Religions

The seraphim share traits with divine beings across religious traditions, from Hindu Nagas and Agni to Zoroastrian Amesha Spentas, reflecting universal archetypes of divine guardianship, purity, and fire.

- Islamic ḥamlat al-arsh: Throne-bearers of God who praise Him continually, paralleling the seraphim’s role as perpetual worshippers.

- Hindu Agni and Nagas: Represent divine fire and guardianship, illustrating themes of protection, purification, and mystery.

- Egyptian uraeus: A fiery serpent worn on pharaohs’ crowns, symbolizing protection and divine sovereignty, echoing the seraphim’s fiery essence.

This cross-cultural analysis shows that fiery, divine beings embody universal themes of transformation and holiness, enriching the understanding of seraphim within a global spiritual framework.

Conclusion: The Seraphim as Transcendent Symbols

The seraphim have evolved from ancient symbols of fire and serpents to exalted beings representing divine love, holiness, and purification. Their journey illustrates the adaptability of religious symbols, shaped by the theological needs of their time and redefined by monotheistic beliefs.

Legacy Across Cultures

- Symbol of Divine Purity: Across Jewish, Christian, and global traditions, the seraphim’s image as fiery beings reflects themes of spiritual purification.

- Inspiration for Spiritual Ascent: Mystics and artists have long invoked the seraphim as a symbol of humanity’s potential for union with the divine.

Ultimately, the seraphim stand as transcendent symbols of divine love and purity, embodying the timeless qualities of faith and reverence. Their fiery wings and ceaseless adoration offer an enduring vision of humanity’s relationship with the sacred, inspiring readers to consider the transformative power of faith in seeking closeness to the divine.